You may have wondered why businesses can be built on importing existing products from overseas and marking it up a lot. Importing is an arcane process! You need to find a reputable source, get and test samples, arrange shipment (if large quantities, it’ll be by boat, which can take a few months) and handle customs paperwork and pay the tariffs to get it off the boat. Then handle delivering It by truck. Agents can handle much of this, but then you have to find, vet and pay them. Knowing who to talk to, and who will talk to you if you’re small, is part of the work.

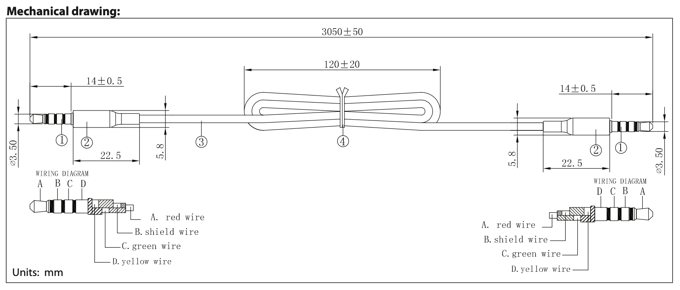

Now take that work and multiply it by 30. In addition to the electronics (no easy task itself), we have many humble components we need to source in bulk for the final assembled Pickup — connectors, seals, screws, magnets, cables, probes, etc. Sometimes you find that there isn’t enough of a component in stock around the world, so they have to make it for you. Sometimes you have to make mechanical drawings to show them exactly what you need done.

Manufacturing is a well-oiled machine once you’ve set up your supply chain, which is a big project. It could easily be a full time job here, and that’s why most companies with volume will outsource it all to a contract manufacturer who can just ship a finished product in packaging for them.

Having made several products, we had a roster of companies we knew we could work with easily, get fair prices and customer service from, etc. But since we last worked with them, the landscape has changed. Consider the two primary parts of Pickup—the circuitboard and the case.

Circuitboard

At their most basic, a board assembler gets your custom circuitboards fabricated, puts the electronic components on those boards (mostly automated with some manual labor for through-hole parts), and tests the assembled parts. Many offer additional services such as more elaborate testing, sourcing and inventorying the parts, and mechanical assembly steps.

My favorite assembler, a family-operated business 30 minutes away, got bought by a bigger company in another state. We got a quote from them that came in higher than what I’d expected based on our past orders, about three times what an Asian company could do and with (no joke) 100 times higher setup fees. So we had to go through the sourcing exercise above all over again, and we didn’t find any better prices (some were higher than Pickup’s retail price) or customer service in the US. Some assemblers didn’t respond at all.

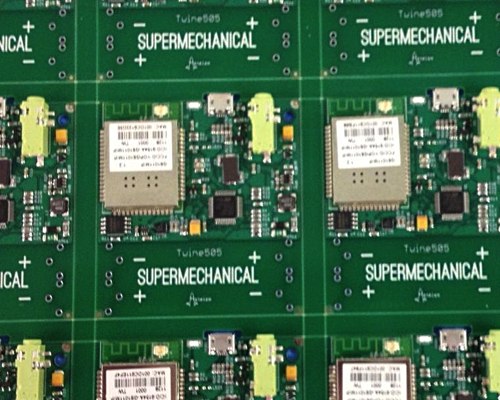

We qualified a scrappy assembler in Shenzhen, China’s famous electronics hub. They source the components for the circuitboards at better prices than we could get ourselves, and have minimal setup fees, that make it easy to iterate on the design. Their responsiveness and attention to detail in making the main boards have been critical for us.

Plastics

For plastics, I’ve used injection molders in Maine, Shenzhen and Minnesota. In contrast to electronics, I’ve found better customer service domestically (though not better prices). We previously used Protolabs for Twine—they have fast domestic production and low tooling costs, but high per-part cost and limits to what they can mold. In hindsight, their moldmaking would’ve been faster than the partner we picked, but I chose our partner in Texas for their fit for our volume, quick local production, and flexibility that will be useful when we develop future products.

Plastic parts have a much higher level of detail and fixed costs, and so the process of making them is more involved than other components:

- We send design files to the injection molder who sends them on to their mold maker, and after some back and forth, we put money down.

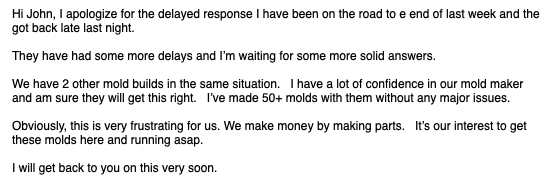

- They carve the molds and send us sample parts (this is where we’re stuck right now).

- Based on our feedback from the sample parts, small tweaks are made to the molds if needed.

- The molds get put on a boat for two months (the most cost-effective way to ship a literal ton of steel), and trucked to the injection molder in Texas.

- We sit down with the molder while they run parts to dial in final parameters and color. Allowing for their schedule, it takes less than a day to actually make our parts.

The primary reason Pickup is behind our production schedule is getting those molded plastic parts. Given these steps, I’d say we’ll be shipping about three months after we get those first samples.

While we may be a small fry to our molder, I suspect that as a family-run business, they’re also a small fry to the mold maker. I apologize that Santa won’t be bringing Pickup this year—our backers’ patience and understanding has been exceptional—but it’s waiting on just a few dominoes to fall.

A small link at the end of the chain

This is the deal—when you’re not big, vendors either make you a low priority or they give you a price so high they don’t expect you to take it (known as the FU quote). American manufacturers can be great if you have volume, but Chinese manufacturers’ willingness to do low volume business supports entrepreneurs better. They invest in the relationship when it’s not as profitable, hoping business will grow. In theory, automation should reduce the cost gap somewhat, but we’re not seeing that reflected in the domestic quotes we got.

Rebuilding our chain now, things will go smoother next time. We’ll revisit domestic if and when we have higher volume so that we can get competitive pricing and customer service, but we’ve built a good relationship with our current board assembler. In a future update, I’ll try to show you more about the mix of foreign and domestic parts and labor that goes into Pickup.

The rest of the work

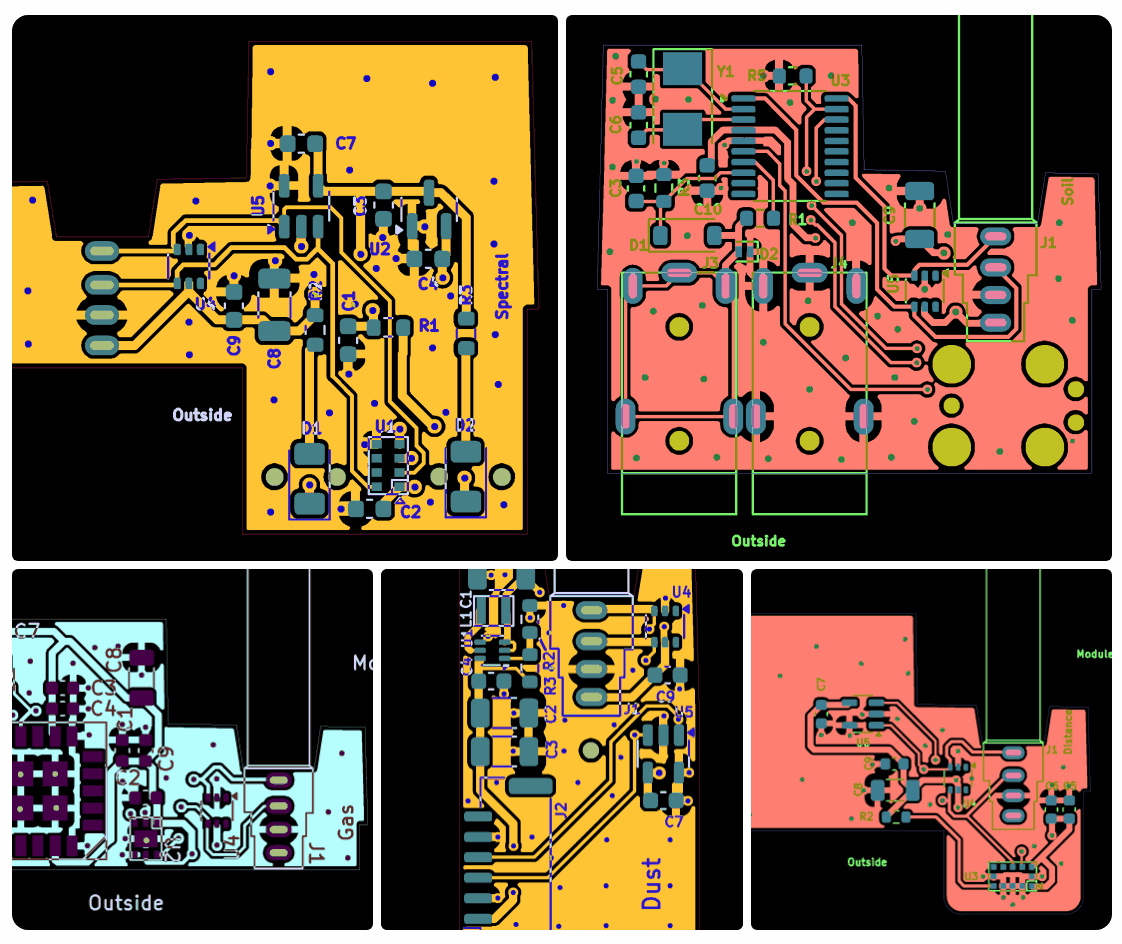

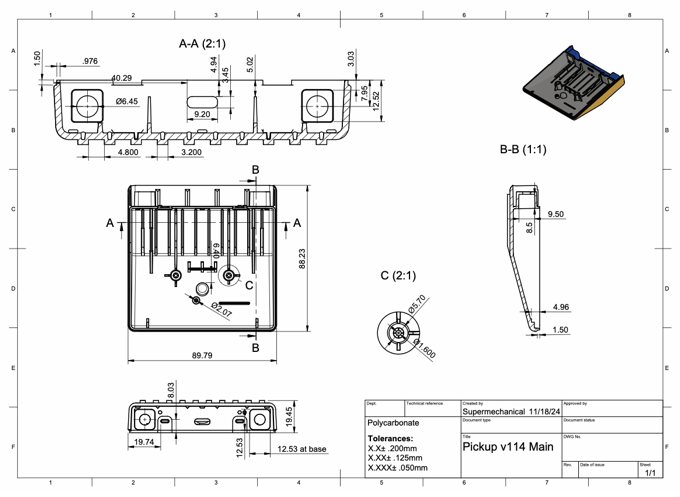

Of course, we’re not just waiting for those molds. We’ve had prototype boards of the sensor cartridges working and tested, and once the functional design was proven, we had to finalize the mechanical design. This takes coordination between Jeremy laying out the boards, and me giving him constraints on size and placement to fit in their cases. We’re sending the production files (those drawings at the top of this update) for all sensor cartridge circuitboards to our board assembler now.

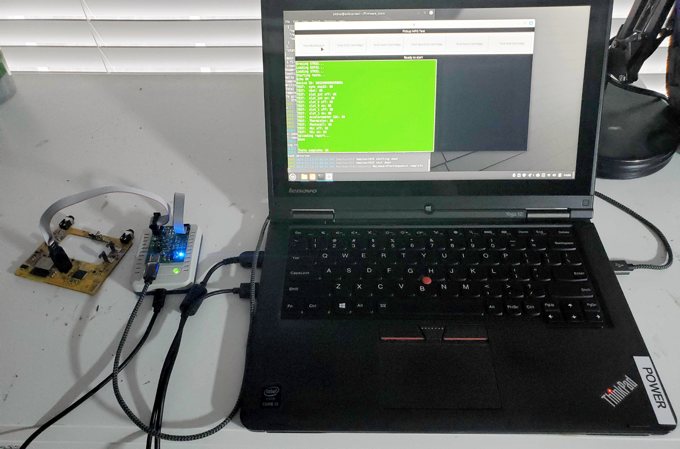

We’re also mailing them the test rig, a programming board attached to a laptop running custom scripts that Jeremy wrote which test the main parts of each Pickup board and collect test data to send back to us. The rest of the production Pickup boards are paid for and the manufacturer is waiting for our signal to build them, which ideally will come after we can do a fit check with the first sample case parts.

Reading list

I’ve previously mentioned the obvious choice here, “Arriving Today”, a book on the modern supply chain by Christopher Mims.

If you want to read more about how products get developed, I enjoyed these articles on Half-Life 2 from Ars Technica — How Valve made Half-Life 2 and set a new standard for future games and Half-Life 2 pushed Steam on the gaming masses… and the masses pushed back — and a recounting of how Valve got its start from one of its original people.

And if at the end of this update you’re getting into the long-read zone, Ed Zitron wrote a passionate essay about how internet services are rotting (language warning):

I believe that the friction we feel on platforms and apps between what we want to do and what the app wants us to do is one of the most underdiscussed and significant cultural phenomena, where we, despite being customers, are continually berated and conned and swindled.

Here’s to building the products, services, and world we want for ourselves, in the new year and every year.

Crossposted from Pickup Kickstarter update #12