Air! Filled with all sorts of little bits of matter, some of which are good for us, and some of which are (increasingly) not. CO2, smoke, allergens, vapors from off-gassing building materials. But we can’t see how much of those are in the air, and so the actions we take to breathe better air are often a matter of faith. When do we actually need to worry?

There are air quality monitors out there, of course. But most of them lack something. They don’t sense all the things I care about (true CO21, VOCs, particulates and humidity), have short battery life, don’t give me control over the data and alerts, or are really expensive.

We conveniently bundled everything we want into the Pickup Air kit reward level. Maybe you don’t care about measuring all of that—Pickup’s flexible, so snap together your own ideal air quality monitor.

What things in the air can Pickup make visible, why should you care, and where exactly would you put it to monitor?

What’s worth sensing?

CO2 is that stuff we exhale, and that plants crave (which is another use for the sensor, especially if you have a greenhouse). It’s also produced by burning fossil fuels, but the pandemic has made us conscious of keeping the density of people indoors low, and CO2 is a good way to measure that. CO2 also can impact our cognitive function and restfulness. (Watching CO2 increase in the bedroom and home office has made me ventilate better.)

Think of the VOC sensor as a digital nose. VOCs can be produced by cooking, paints, cleaning products, air fresheners, pesticides, building materials and furnishings, cosmetics, and 3D printers. Exposure can cause headaches, respiratory problems, and memory impairment. VOCs can also be generated by natural organic processes like food spoiling or fermentation, which suggests some kitchen experiments…

PM2.5 is particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns, which might be dust, pet dander, aerosols, car exhaust, smoke, poorly ventilated gas heaters, or bacteria. This is the size at which it can get into your lungs and bloodstream, so exposure can cause not just irritation but long-term health problems. Not to scare you, but a study2 called ambient PM2.5 “the world’s leading environmental health risk factor.”

Too much humidity is uncomfortable, keeps more particulates around, and provides good growing conditions for mold and bacteria. Too little humidity is uncomfortable and dries out the nasal membranes which filter out viruses. Managing humidity may be a cheaper way to feel comfortable than cranking the AC. Of course, it’s also important for food storage.

Aside from detecting these things in the air for their effect on us, they’re useful for measuring the effectiveness of systems designed to remove them, or even controlling them with automation—say, switch on an air purifier when needed.

Where could you monitor air quality?

So we know what’s worth measuring. Where can we put a sensor?

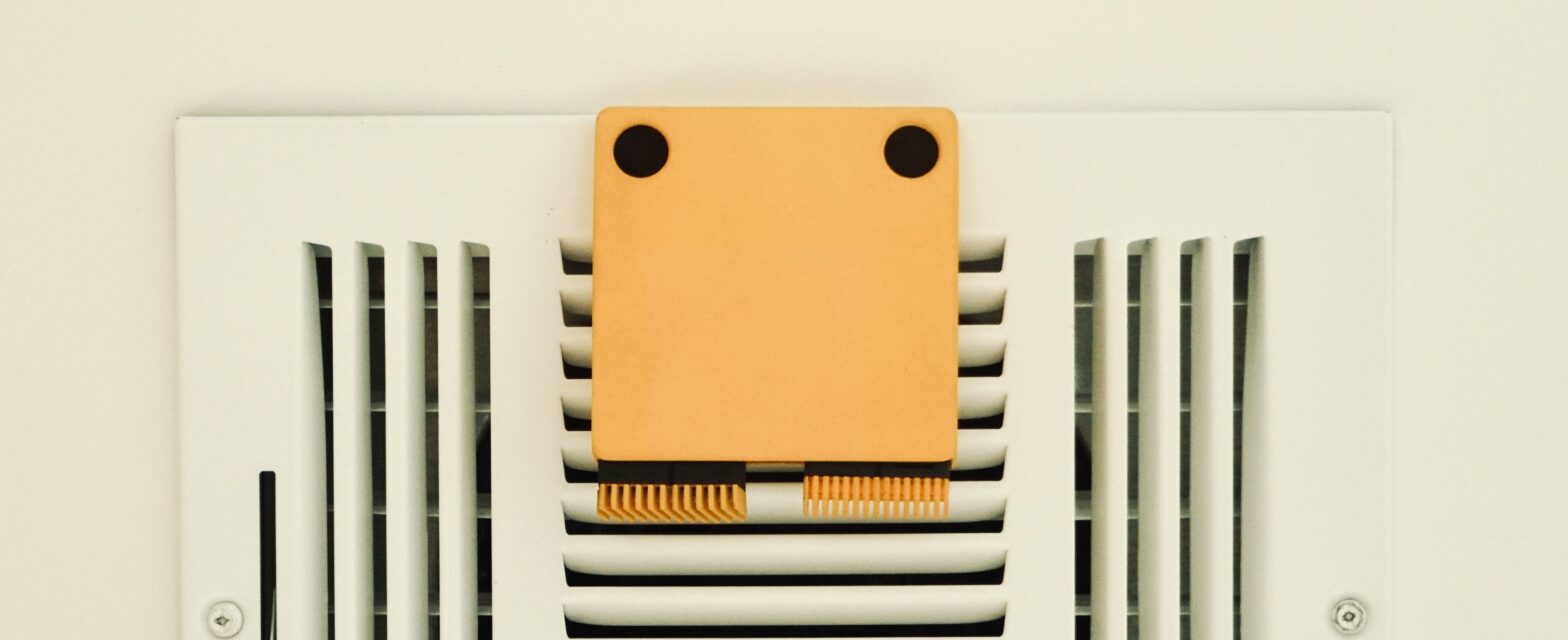

- Measure the HVAC filter’s effectiveness at removing particulates, and how it changes over time.

- Monitor CO2 build-up in your indoor environments, how ventilation affects it, and correlate it to your restfulness and productivity.

- Map temperature differential across air vents to find hot spots.

- Measuring the VOCs coming off a 3D printer to determine whether you have enough ventilation.

- Compare a range hood’s noise level vs. effectiveness at reducing VOCs/particulates.

- Measure how much houseplants help reduce CO2 levels.

- Detect spoiling food, ripening fruit or measure fermentation activity.

- Stick a Pickup on an air vent in the bedroom (magnets!) and on the air return, to see how many particulates the HVAC filter is removing from the indoor air.

- Something I haven’t thought of, but you have. That’s why we made Pickup to be flexible. Tell me your idea.

You can get the Pickup Air kit (which is a Pickup environmental monitor, a CO2/humidity cartridge and a PM2.5/VOC cartridge), or other combinations of sensors, on Kickstarter now. We wanted to make high-quality air sensors available to everyone, so they’re priced low for the campaign, but will probably go up in price afterwards.

- I use the term “true CO2” because many CO2 monitors don’t actually measure CO2. Instead, they use eCO2 sensors that detect VOCs (volatile organic compounds), and based on the assumption that VOCs are mostly generated by humans, they have a formula that estimates (that’s what the e in eCO2 is for) the amount of CO2 that humans would be exhaling. The problem with that assumption is that VOCs are often produced by sources that don’t also produce CO2, like cleaning products, paints and cooking. An NDIR CO2 sensor like the one Pickup uses measures actual CO2. ↩︎

- “Source sector and fuel contributions to ambient PM2.5 and attributable mortality across multiple spatial scales”, Nature Communications, 2021 ↩︎